Taking the Deforestation Out of Avocados

Everyone loves avocados. They taste great, and they’re good for you, but our ravenous demand for them is prompting farmers in central Mexico to chop forests, and that accelerates climate change. It’s a demand-driven problem that requires demand-driven solutions, but that doesn’t mean you have to give up the guacamole just yet. Here’s a look at both the challenge and its solutions.

25 August 2016 | What’s small, green, famously healthy, and deceptively destructive? Avocados, believe it or not. The benign-looking fruit has captured worldwide attention in recent weeks after revelations that America’s insatiable taste for guacamole is prompting farmers to chop forests in central Mexico – and funding narcoterrorism in the process.

After initially disputing the reports, Mexican avocado growers have resolved to make their operations more sustainable – but how? After all, the problem begins with foreign demand, and it extends beyond avocados, as Bolivian chef Kamilla Seidler pointed out at the Aspen Ideas Fest in Colorado, where she described the “Quinoa Effect” that has driven the price of a kilogram of the fashionable grain from $1 to $11 in La Paz – a boon to growers (or, more often, middlemen) but a bust for working class Bolivians who rely on quinoa as a staple food.

The solution, it turns out, won’t come in the form of a silver bullet or tidy quick fix. But the necessary ingredients are within reach: consumer self-awareness; lessons learned in the beef, soy, and timber trades; new financing mechanisms enshrined in the Paris Climate Agreement; and a dash of entrepreneurial spirit blended with some time-tested lessons from forests and the communities who have sustainably managed them for centuries.

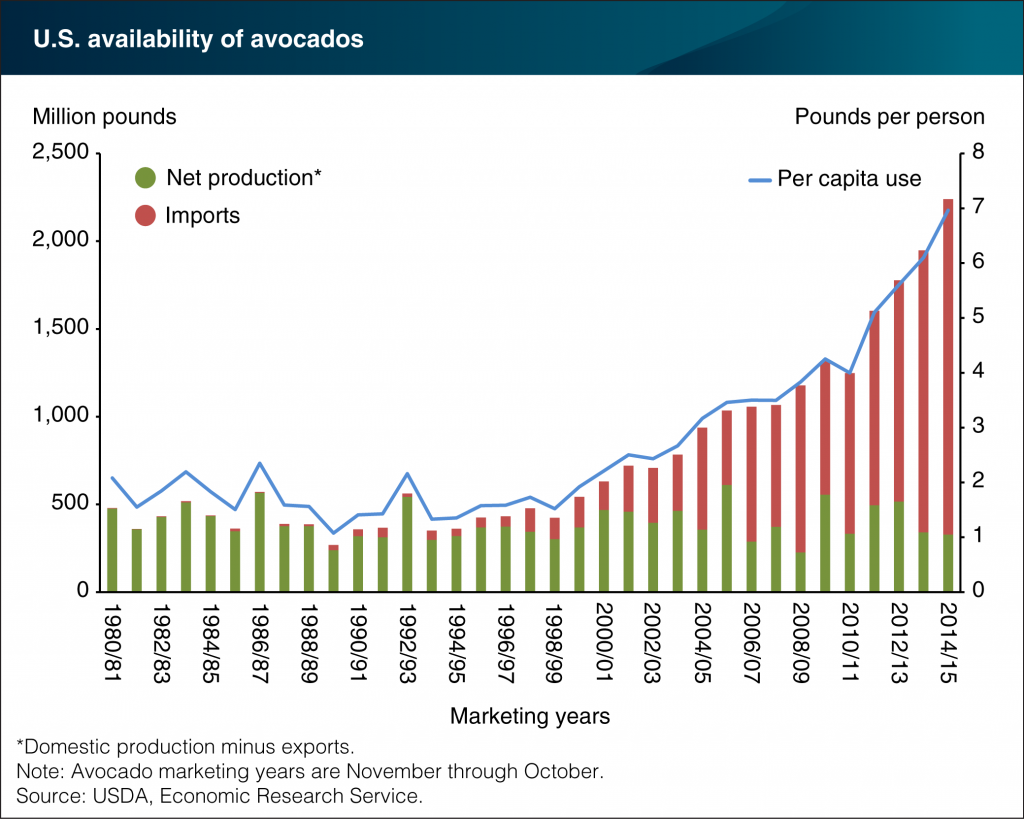

America’s love affair with the avocado dates back well beyond the quinoa boom – and while it began within U.S. borders, it was Mexican imports that allowed that relationship to flourish. Avocado consumption has doubled in the past 10 years and is nearly four times higher than in the mid-1990s, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The average American consumed nearly seven pounds of avocados in 2015, compared with less than two per year prior to 2000.

The Demand Side: Creative Consumers

Americans could “buy local”, but that won’t make a dent because California is the only US state that produces avocados on a large enough scale to matter, and its thirsty orchards face challenges of their own.

They can also substitute, according to Brazilian chef Paulo Machado, an expert on Latin American cuisine and member of the sustainable food initiative Cumari: From Rainforest to Table. He cites a fruity reinterpretation of guacamole that uses a fraction of the avocado typically found in the dish. The recipe, which Machado inherited several years ago from a Mexican friend during a period of runaway avocado prices in Brazil, substitutes mango, peach, and the savory texture of papaya to fill out the rest of the body.

And at the grocery store, consumers can also mitigate some of the environmental and social costs of Michoacán’s avocados by purchasing only those that are certified organic. Admittedly, organic certification has its shortcomings – for example, it doesn’t explicitly address deforestation – but locals point out that organic methods can address certain other negative consequences of avocado farming tied to public health, soil quality, and biodiversity.

Suppliers can also lift a page from the larger soy, palm, and beef sectors, which have embraced products that are certified as “sustainable,” but such certification efforts aren’t easy to set up.

The Supply Side: Funding Sustainable Agriculture

Another part of the solution emerged at the Paris climate talks, where companies like Unilever and Marks & Spencer pledged to source raw materials from states and countries that can prove they’ve slashed deforestation, regardless of which commodities are causing it. To overcome start-up costs, they embraced a program known as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+), which was embedded in the Paris Agreement and aims to slow deforestation by tapping carbon finance to promote sustainable agriculture.

Although often characterized as “paying people to not chop trees,” the acronym covers a diverse array of mechanisms that divert finance into activities designed to save forests – from actively patrolling them to helping farmers become more efficient in managing the land they have to jump-starting certification programs. Donors have committed nearly $6 billion to 10 key tropical forest countries – including Mexico – to fund REDD+ readiness efforts aimed at boosting the capacity of governments to more effectively manage their forests, with an eye toward achieving long-term sustainability.

“REDD+ donors are interested in providing the incentive for governments to prioritize what is, in many ways, in their long-term interest anyway: conserving their forests by directing intensified agricultural production to areas already degraded or under cultivation,” says Brian Schaap, a Senior Associate with Forest Trends.

In its climate action plan, Mexico explicitly mentioned using REDD+ to promote sustainable agriculture in agrarian and forest collectives known as ejidos, which are legally owned by communities and account for roughly 70 percent of the country’s forested land.

But while REDD+ can help finance sustainable forest management, it’s not a panacea that can protect against the effects of consumer demand, says Naomi Basik Treanor, Program Manager for Forest Trends’ Forest Policy, Trade, and Finance initiative.

“Sure, it’d be great if countries stepped up enforcement efforts and got rid of laws that contradict each other, and if consumers changed their spending habits,” she hypothesizes, “but a real solution would be demand-side policy that ensures only legally and sustainably sourced products make their way into consumer markets.”

These kinds of policies already apply to timber imports in the U.S., EU, and Australia, and some conservation groups are lobbying for similar laws to promote responsible agricultural supply chains.

Diagnosing the “Avocado Fever”

“We want to focus on deforestation, but it’s only part of the problem,” says Nacho Simón, a Michoacán-based agricultural advisor with the group GAIA who teaches organic farming methods through workshops and courses across Latin America. He expresses concern over the long-term impact of herbicide residues in Michoacán’s porous volcanic soil, and cites high rates of anencephaly and leukemia in two of the state’s major avocado zones. Organic farms, which forego industrial herbicides in favor of natural inputs, account for only a small fraction of avocado cultivation in Michoacán – 7,000 to 8,000 of 130,000 total hectares, according to Simón.

And while Michoacán’s organic avocado orchards are reducing the volume of chemicals exposed to local groundwater, many are failing to achieve another one of GAIA’s tenets: biodiversity. As high avocado prices make monoculture increasingly lucrative, Simón says it’s been a challenge to persuade even organic farmers to continue cultivating a variety of crops – to promote beneficial biodiversity and, in the process, grow food for their families. In addition to the thousands of hectares of forests that have been cut down and converted to avocado orchards in the last 15 years, Simón says a growing numbers of farmers are switching from maize to avocado for export. He marvels at the paradox of having to buy conventional produce from Walmart because your land is devoted entirely to growing organic avocados. This, Simón says, perfectly illustrates la fiebre de aguacate – the avocado fever – that has taken hold of Michoacán’s agrarian sector.

Connecting Farmers and Consumers

One creative way to connect small farmers with distant markets is through tools like Putting Amazon Indigenous Producers on the Map, an interactive map developed by the Coordinating Organization of the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon Basin (COICA), Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), EcoDecisión, and Forest Trends with support from USAID.

Chris Meyer, Senior Manager of Amazon Forest Policy at EDF, says 150 producers have been mapped so far, with more additions coming every month. The new initiative has already helped connect the Uncommon Cacao group with Peruvian cooperative Kemito Ene, whose indigenous farmers are poised to earn up to 20 percent more income as a result of the agreement. Advocates say this is the kind of incentive that can help local communities continue practicing agriculture in a responsible, sustainable way, protecting surrounding forests in the process.

“There are a number of coffee and cacao producers and associations who have certifications that are ensuring sustainable production,” Meyer pointed out in an email. One prominent example is Runa, an ethical producer of a tea-like beverage derived from guayasa, which sources the Amazonian leaf from a co-operative of small, sustainable producers. Guayasa is a shade-grown shrub planted in biologically diverse “agroforestry” plots, alongside bananas and other crops, that thrives in a comfortable symbiosis with existing forests, rather than at their expense. Meyer concedes that guayasa doesn’t suffer from the same demand pull as avocado; still, Runa’s growing success suggests that consumers are hungry for “superfood” products that are sustainable – not just healthy.

As for the interactive map, Meyer hopes it will help multiple actors – from consumers to restaurateurs to distributors – connect with sustainably produced Amazon ingredients. Another project taking the work out of identifying responsible small producers is Canopy Bridge, the non-profit whose website hosts the Amazon map. But its sourcing network includes sustainable producers located well north of the Amazon, including central Mexico, opening the door for avocado growers looking to stand out from the crowd by virtue of their environmentally friendly farming practices.

See how initiatives like Cumari: From Rainforest to Table are trying to drum up extra recognition – and income – for Latin America’s forest stewards:

The Wicked Challenges

Back in Michoacán, the organic farming advocate Simón agreed that demand is the primary culprit.

“The biggest pressure is economic,” he says. “Because of the very high prices avocados bring, of course people are going crazy over them.”

Simon didn’t mince words when asked about new commitments from APEAM, the Mexican trade association, to double down on their reforestation initiative and work with the government and state university to develop limits on future expansion.

“It’s all purely political; this is political posturing,” he says. “If they had had the will to [take these steps], they would have done it 10 years ago.”

To date, Simon says the group’s reforestation efforts have been geared more toward publicity than meaningfully restoring carbon stocks.

“You’ll see 1,000 saplings planted along city streets, and meanwhile in the hills, where nobody sees, 10,000 enormous pines get felled,” he says. “It’s pure garbage.”

And then there are the notorious Mexican drug cartels, who, through a combination of extortion and violence, compel avocado farmers to maximize production.

“Not only do [these criminal enterprises] offer incentives to local communities that exceed those of their normal, legal income streams, but evidence from other countries shows they may exert considerable pressure on those who either refuse involvement with the trade or deny gangs their cut of the profits,” says Basik Treanor.

One Michoacán farmer, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal, reported last week that an engineer working with avocado farmers was murdered just days prior, and says killings and kidnappings are a daily occurrence.

“Here, people live in a situation of terror,” he says.

While the slow wheels of policy and business practice turn, it’s up to consumers to make thoughtful and informed decisions – whether at the grocery store or at their favorite Tex-Mex chain. For now, the safest bet is to go easy on the guacamole. Michoacán’s forests will thank you for it.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.